CosMuseum Project: Memories and Souvenirs from planet Earth - Juniper publishers

Journal of Trends in Technical and Scientific Research

Abstract

The etymological origin of the word museum is muse. If the muse of our space era is the Cosmos itself, then a CosMuseum

is our proposition for a nomad museum in space, carrying

artworks-memories from Earth’s civilization. Remembering that every

additional gram of cargo in space expeditions is extremely expensive,

the lighter the cargo is, the more economical the expedition will be.

Conclusion: we cannot carry Pyramids and Parthenons to the CosMuseum.

Thus, this paper is proposing Michaloudis cultural cargos for this

imaginary museum in space; sculptures made of the lightest solid on

planet Earth together with a combination of digital images from Hence’s

artworks. The author’s first immaterial artworks are directly influenced

by Cycladic art. The co-author’s artworks are based on the traditional

medium of oil on canvas, which are based on earthly constructions of

termite mounds. In this paper we’ll present some of their artworks and

posit them as potential precursors for a cultural cargo from our

(h)Earth.

Keywords: Museum, Catastrophe, Silica aerogel, Periphery, Souvenir, Memory, Canvas, Termite mounds

Introduction

Dr. Ioannis Michaloudis is a forerunner in research

regarding the use of materials that bridge art and the new sciences of

space. The primary material currently dominating his research has been

developed by NASA, the nanomaterial silica aerogel into which he sculpts

his aer( )sculptures. Ian Hance is a PhD student at Charles

Darwin University under the supervision of the author. His works consist

of oil paintings on canvas based upon the subject of termite mounds,

native to the Northern Territory, which unknown tourists adorn with

found objects in various arrangements. The third co-author, Christine

Tarbett-Buckley is the Head of Collections at the Museum and Art Gallery

of the Northern Territory and a Research Fellow at Charles Darwin

University. She has a background in archaeology, art and law and

museology with research interests in the evolving concept of the museum

and the sustainability of museum collections into the future. Dr.

Katerina Koskina is an Art Historian-Museologist and in nowdays the

Director of the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Athens, Greece.

She was the curator of Michaloudis’ solo exhibition 11 aer( )sculptures

in the Cycladic Museum of Athens back in 2006. This paper interrogates

the practices/research of the two artists with the hypothesis that it

will be necessary at some time, in the not too distant future, to

situate a museum in space both as a repository of both original artworks

and as simulacra for works too large or weighty to be installed. We

maintain that the physical constraints will not allow for the

installation of art pieces or architecture that are typical to the

current museum arrangement. It is therefore our contention that replicas

and original art need to be rendered in weightless materials, digital

records, holograms, light projections and other media yet to be

discovered. The last sections discusses the natures and contexts of a CosMuseum

as seen by curators Christine Tarbett-Buckley and Katerina Koskina.

Thus this paper is a discussion of themes and contexts from two distinct

perspectives―that of practising artists and of museum professionals.

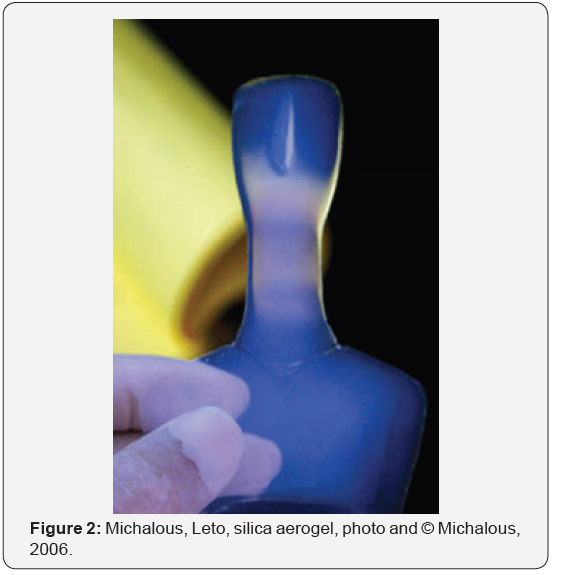

Michaloudis is a sculptor combining art with

technology by using the space era nanomaterial silica aerogel. It

constitutes of 99,9% air and 0,1% glass and has been extensively used by

NASA for the collection of stardust. When he was first introduced to

the material he was permitted its use only for the creation of small

size artworks. His concept of creating moulds of Cycladic figurines was a

result of the convention of their size. He suggests that these

primitive figurines function as a symbol representing the self, one that

is widely recognizable by the

public as such. This recognition enabled him to promote his

technique through utilising symbols familiar to the observer to

create an overarching theme. He called his work aer( )sculptures

as the only source is light in the absence of material. He chose

silica aerogel as a contrasting material with marble to create a

dialogue between the lightness of the aer( )sculpturess and the

weightiness of the marble figurines.

The incentive force of sculptural metamorphosis of the

Cycladic form may have plotted the chronological course from

the historically-loaded material of marble to the nowadays

space technology nanomaterial, suggesting a parallel journey

that started from the authentic form and finished as a “fake”

copy. To the artist, this journey could be summarized through

the creation of a pun on the Greek word plastos that has the

dual meaning of ‘sculpted/modeled’ and ‘fake’, with particular

reference to tourist souvenirs. The discussion of visual records

in digital photography speaks also about disappearance,

namely the original material that is left behind or perceiving

the original in an altered form, from a peripheral viewpoint.

Both artists and the one of the curators are situated in a unique

positioning of periphery being at the last frontier of Australia,

Darwin in the Northern Territory. Within this context, the

periphery functions as a stimulus to both produce art and to

secure its preservation. The dialectics of materiality/nonmateriality

of original to copy are examined through the

workings of ambiguous space, colour and form in the discussion

of Michaloudis’s sculptures and Hance’s oil paintings on canvas.

The materials discussed include the primary material of

silica aerogel in Michaloudis’s aer( ) sculptures and Hance’s

oils on canvas and the digital images he captures his subject

matter with. Then follows a discussion of the formal, nonformal

aspects of the imagery based upon Cycladic figurines

in their reference to Neolithic fertility idols and how both of

these references find their poetic connections as memories and

souvenirs. These memories and souvenirs from planet Earth

are to be placed in a hypothetical museum of the future named

here as CosMuseum.

Views from the Periphery

The view from space of Australia on the television screen is

so familiar and central whether that is on the weather channel

or the news channels yet its cultural positioning in the western

perspective has always been considered marginalised, (Figure

1). Historically it was one of the last continents to be mapped

by Europeans. To Australians, the last mass of Oceania was

always their centre and any effect of the perceived periphery

on their culture will not be discussed here. However, the

significance of memory in the oral tradition of Australia’s

Indigenous peoples will form part of the argument for inclusion

of souvenirs and memories in the museum, to offset the sole

reliance on digital data. Darwin’s remoteness in this largest

of all islands stands as a personification for the remoteness of

space or planet Earth’s remoteness within our solar system and

beyond. The experience of the materiality of visual cultures

from the “centre”, that is the rest of the world, has always been

Eurocentric.

The Australian viewer’s experience of international

artworks has required leaving this island in order to see such

works physically. For the rest of the time this experience has

been substituted with the experience of the photographic

reproduction or online digital records [1]. It can be argued

that an artist in this context of the periphery is in an excellent

position to reflect on what are the possibilities beyond this

horizon; as being located on the periphery can provide a

clearer picture of the whole than can be experienced within

the confusion of the centre. The periphery can be a stimulus

to produce art. The periphery of Earth in the edge of space is

addressed within Michaloudis’s works while the subject matter

of termite mounds for Hance’s paintings are peripherally

located on remote areas of the highways of the tropical north of

Australia, (Figure 2&3). Hance’s costuming of these mounds is a humorous expression of tourist’s desire to see the nakedness

of these anthropomorphized mounds covered with clothing

and other materials. The concepts of distance and tourism

are discussed later in nostalgia, memories and souvenirs. Art

itself can be considered as a peripheral activity in that it has

a secondary or removed aspect from the primary source of

observation.

Another view of space that is clearer from the periphery is

the view of the night sky/space itself. Unlike most metropolises,

Darwin has relatively little night light pollution and even a

short drive out of Darwin produces excellent views of our

solar system and the Milky Way. The primordial contact that

humanity has with the cosmos here is visually much more

pronounced. The dialectics of natural light and artificial are

brought into sharp contrast by light pollution. The view of

space from major centres of the world is compromised by this

pollution. For this reason it is unsurprising that the telescopes

on Earth are situated in remote locations or placed in orbit

around the earth, again at the periphery.

Catastrophe: breaking materiality and remoulding immateriality

The initial colonialization of Australia can be considered as

a catastrophe for the culture of Indigenous Australians. There

have always been catastrophes for other cultures historically

with the disappearance civilizations and their artefacts, and

possibly with the merging of new cultures. The possibility of

cultural disappearance of any of the world’s societies is just

as concerning in the twenty-first century as at any time in the

past. It is with this threat in mind that the author’s proposal

of a nomad museum containing artworksmemories is a more

urgent consideration than an “ark” of artefacts. What these

artworksmemories will be made up of -or rather their imagined

possibilities- are discussed in the following.

The word terroir (from the French word for “earth”) evokes

memories of flavours/scent of the terrain. All the earthly

ecosystem factors that make up the characteristic of a product,

is terroir. In the author’s case, the cloudlike silica aerogel carries

the scent of earth’s sky as seen in Figure 2. In the co-author’s

case, the product is oil paintings of termite constructions

(mounds) made of earth in the Northern Territory (Figures

3&4). We see these residues or flavours as a kind of terroir, a

kind of subtle overtone or undertone rather like the complex

flavours in wine, forming a subtle metaphor for the “associative

radiances” or a memory of the earth itself. The catastrophic

breaking and scattering mentioned later as part of these

nostalgic memories speaks about the processes of creativity

itself: the other side of the coin of creating is destroying or

“breaking the mould”. In Michaloudis’s practice, the very solid

steel mould has to be “broken” to reveal the magical nonmateriality

of the silica aerogel sculpture. In Hance’s works the

visual breaking up of the space and formal 3D properties of the

termite mound /mould constructions into visual metaphors,

coupled with their abstraction into bidimentional painting is

the complement to the formative properties of Michaloudis’s

sculpture. The discussion of the dialectics of materiality/ nonmateriality

through these properties follows: in the author’s

case, the effects of light in a space/atmospheric medium of

silica aerogel and in the co-author’s the earth bound medium of

oil colour in its application to this abstract space and form will

be discussed below.

Dialectics of materiality

Silica aerogel consists of 1 per cent glass and 99

per cent

air, making it the lightest solid material on Earth [2]. The

scattering of light as seen in the Rayleigh effect is part of the

material properties of silica aerogel in which the source of light

changes the colour depending whether it is seen against dark or

light. In Michaloudis’s Leto (Figure 2) the ethereal blue quality

and its translucency contrasts against the suggested weight

of the Cycladic form when it is set against a black background.

The opposite complementary color that makes up the Rayleigh

scattering -gold yellow- is seen as a formal edge reflecting

against the formless black of space. The edge suggests skin or

surface; however, the skin or surface of the works is almost

invisible whilst the interior space of the works as coloured

volume or mass is poetically amplified. Similarly, the analogy

between the skin of the anthill construction with its clothing

and the skin of paint both conceal and reveal space as a volume

within Hance’s paintings (Figures 5-7).

Thus, Michaloudis’s works are ambiguously both formal

and formless, similar to vapour or smoke. When these works

are set against the black void, their conflicting qualities speak

of the spiritual and the dialectic of material/mystical. These

properties stress the function and the binary opposites of

colour as complementary and function as an expression of

the spiritual, abstract and perhaps mysteries of the cosmos

via their ambiguities of space and hue. In Michaloudis’ works,

many of the sculptures and artworks represent symbolically

an anthropomorphised female figure in some of the Neolithic

Cycladic figurines. This symbol can also be located in Hance

works through the termite mound functioning as a “Mother”

form. Within this reference we can locate other fertility idols

such as the Venus of Willandorf. Michaloudis notes that his

Cycladic figurines similarly reference a symbol for the self

which is widely recognisable and resonate with the public.

That there are references to James Lovelock’s hypothesis of

Gaia, or, put in a more poetic way, Mother Earth, in addition to

this original symbol of the fertility goddess. The Mother Earth

reference adds poignancy to the sculpted and dematerialised

images that could be placed in the CosMuseum. In Hance’s case

the representation of these anthropomorphised figures of the

termite mounds is the counterpoint to the ethereal qualities of

the silica aerogel sculptures mentioned previously.

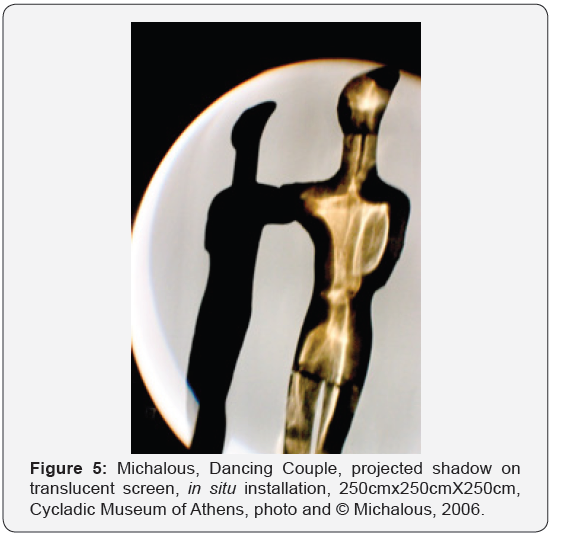

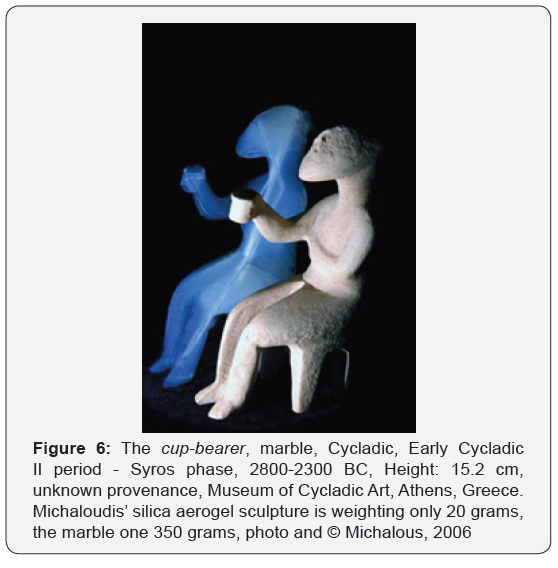

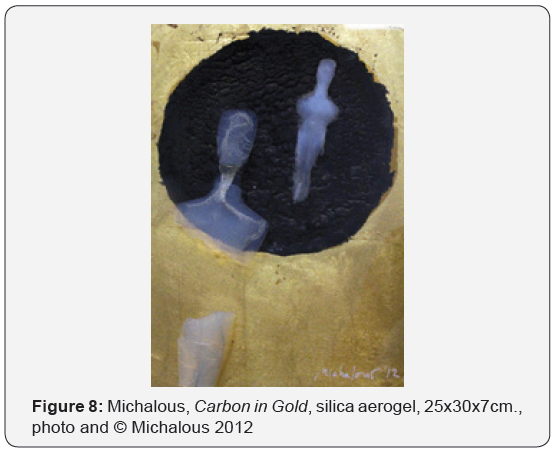

In Michaloudis’ work the cup-bearer, (Figure 6) the

dialectics of the weight of solid marble and the ethereal light

qualities of the silica aerogel provoke feelings of ambiguity

in its relationship to the density of the souvenir as an object

embodying a sense of memory (and terroir). Both objects are

seen in Figure 3 set against void or black space, which itself

holds both formal and informal connotations in its reference

to the concepts of the formlessness and its mutability [3]. In

Michaloudis’ artworks the figures/constructions are nearly

always seen against these black rectangles ovals and squares

which actively reference either the cosmos in a formal way or the void in its connotations of disappearance. Form

functioning against the void and the suggested “memory” of

an original form plays with the ideas of plastos in this work―

“fake” as in a souvenir taken from the original archaic marble

Cycladic sculptures. These are copied into tourist market

copies as souvenirs for sale. From these copies Michaloudis

makes a mould (memory) in which the silica aerogel is cast.

The point being here that material souvenirs are very different

from memories, and the authors hypothesis asks whether the

artists operating on the periphery are in a more advantageous

position to consider the “collection” of the whole; say of digital

memories and works of art in space age materials, not just

souvenirs in their materiality Two works reference the duality

of the past in the present and extend possibilities for their entire

representation within a future museum. The Dancing Couple in

Figure 4 and Figure 5, through its use of space age material

recreates an original form as a duplicate of a missing/lost

“idol” which produces a shadowed reflection as an immaterial

duplicate. These artwork regenerate the past through their

inclusion of lost elements of cultural icons. Their resemblances

in the present converge as an idealised representation for the

future.

Memory in Future Time

The materiality of memory in Michaloudis’ works are

discussed in the following catalogue‘s text by the curator

Katerina Koskina for his solo exhibition 11 aer( )sculpturess in

the Cycladic Museum of Athens, back in October 2006. “Ioannis

Michalou(di)s is one of those contemporary artists who though

espousing international visual inquiry and language, and

indeed is involved with their most recent experimental and

scientific applications, remains at the level of idea and of form

a supporter of local culture. Thus, from his interdisciplinary

experience and training in both art and science, works have

emerged that literally hover between the past and the future.

This is due in large part to the material to which he was first

exposed in a research at MIT and immediately began using

silica aerogel., But Michalou(di)s, as he prefers to sign his

surname, by contracting it, as he does also with the title of

his recent works - voluntarily trapped in a game of knowledge

and chance, of etymology and joke, was fascinated by this

particular material, which looks like solidified air and is

widely used by NASA because of its insulating qualities. Silica

aerogel, although ubiquitous in space and high technology, is an

unknown material and a scientific paradox for artistic creation,

despite its truly magical image and texture, which allows it

to “transform”: the painted skies of the Venetian School into

virtual reality. And yet its basic constituent, silica, for all its

fragility, is a material of high durability to time, a material with

continuity and memory. Perhaps this particular characteristic

of it makes it most suitable for serving a diachronic value such

as art.

In an age when everything aims at dematerialisation,

this material composed of 99% air and 1% glass follows the

opposite course. In essence it “materialises” “nothing” and it

owes its plasticity not to its principal ingredient, air, but to that

minimal percentage of glass, which gives it “body”. That is why

Michalou(di)s has called his works aer( )sculpturess, revealing

both their constitution and the sidereal origin of his material.

A material that exists pre-eternally in the universe in the

form of particles, but whose present form is so recent that it is

considered a material of the future.

However, what is more interesting for the viewer of the

works is not the composition or the provenance of the material,

for all the admittedly alluring image it offers, but the way

in which the artist incorporates it in the creative process.

Michalou(di)s uses the astral material to represent Cycladic

figurines, that is works of the 3rd millennium B.C. This is not

the first time that he feels that the ancient form demands from

him a metamorphosis. The archetypal form of the Cycladic

figurines, which is the cultural nucleus not just of Greece but

if the whole of the West, appears because of its abstraction

eminently timely and suitable for “habitation” by a supermodern

material. Michalou(di)s apparently conceived this

message of the timelessness and modelling of form, which

inhabits the collective subconscious, when he decided to

predict the future image of the figurines by “embracing” them

with the nostalgia distinctive only of a Greek who has lived

abroad for many years.”

Chaos as background

In both the black ground of the sculptures and paintings,

(black being an amalgamation of all colours of the spectrum

in an additive way) Michaloudis’ sculptures also experiment

with the disappearance of colour and light. In Michaloudis’

sculptures the disappearance or flux perhaps between the

polarities of light contained in the aerogel produces the

complementary colours of blue and a golden orange (depending

on which view is taken of the work). This mutability or

shifting of view is an expression of the spiritual values in

our contemplation of the cosmos, or at least the importance

of a shifting perspective underpinned by the dialectics of

materiality/non-materiality. The description of Michaloudis’

aer( )sculpturess as being the only source of light in the absence

of material or a non-materiality of the aerogel forms a poetic

expression of both the spiritual form or memory. The painted

black backgrounds of Hance’s work similarly reference both

void and formal space at the same time. They also reference

the in-between space of the canvas itself covered by pigment,

the sensed space of advancing forms surfacing in the picture

plane. Rather than receding back into the picture plane as in

Renaissance perspective, the volumes established sit forward

in ambiguous space, (Figure 7). Glossy transparent backs and

solid black pigments combined with their relative “silvers”

explore this in-between space. Other artists such as Gerhardt

Richter and Rembrandt have used the ambiguities of black.

Rembrandt’s tensions of warm and cool blacks similarly give life

and articulation to an otherwise void of black. Pierre Soulages similarly used impasto glossy blacks against flat blacks to

explore formal and spatial properties. The void also speaks

about disappearance and if we accept Baudrillard’s concepts of

reality in our age (the Anthropocene) as disappearing behind

the black screen of the Internet and digital media, there is

poignancy inherent in the black screen or black rectangle of

painting in the sense of loss or absence [4]. Black also speaks

about the invisible and as such invokes the non- material or

spiritual. On the other hand, a texture and impasto surface in

black paint draw attention back to the surface and thus speaks

about the weight or gravity of the artwork. The black circle in

Michaloudis’s gold Cycladic figurines holds expression of the

chaos of the void whilst simultaneously creating a tangible

space established by the perspectival positioning of the two

Cycladic figures (Figure 8).

The weighty solid panel made of scorched wood in Figure

8 is covered in gold leaf accentuates the weightlessness and

suggested movement of the silica aerogel figures. Gold in

itself sits ambiguously between form and light in its reflective

properties and its physical metallic property. Conceptually

it references the spiritual in its associations with cultural

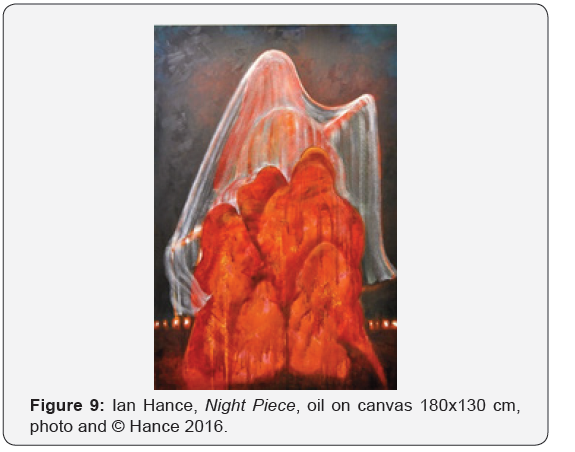

symbolism of the divine. Not so in Hance’s work Night Piece

(Figure 9), in which materiality references the purely secular

in its references of the earthly grotesque soil presented a

basic human female form. The dressed up figure is set within

the space of the periphery of a township against a warm

black that functions as both atmosphere and solid humidity.

This black is suggested by a solid impasto paint surface and

includes visible fluid runs of paint. Again black is used in its

ambiguities of weight and weightlessness. The singular f igure

evokes a feeling of solitude and isolation that also expresses

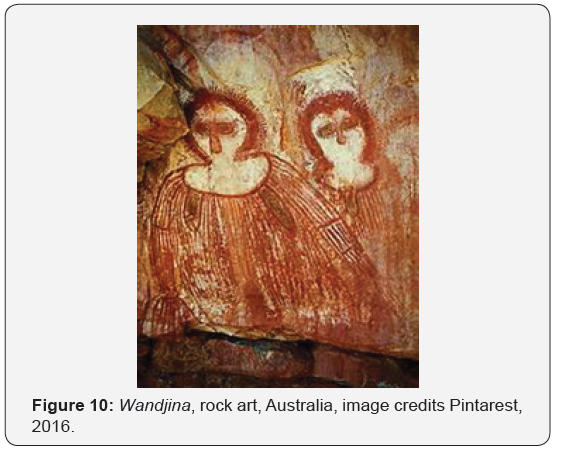

the periphery. A connection to ancient images such as the

Wandjina (Figure 10), which is executed in a similar medium,

that of earth/red ochre, reinforces concepts of earth bound

materials. However, these Wandjina are representations of

spirit beings grounded in earth’s palette; a counterpoint to the

spiritual blue of Michaloudis’s Cycladic figurines. The Wandjina

figures are earth bound in more ways than one; being painted

on a rock shelter -like the pyramids and the Parthenon- they

can never be transported to a space museum.

Further to the dialectics of materiality/non materiality, the

idea of translating the digital images of the works into light

images for a repository, a CosMuseum in space is proposed in

order to hold memories of earthly constructions as art. In this

process of the copy of a copy-or simulacra-the memories of

earth and paintings produce nostalgia and an ironic reflection

of what is left behind. Analogous are the processes of the

mounds themselves as aspiring to become space themselves,

both internally and externally. The reproduction of original

works based upon the digital recording (a copy) are then

copied by a digital photograph (a copy) to be reinvented into

the digital trace that finally appears on the screen in the form

of RGB light that constitutes pure digital data. Through these

methods we enter the arena of the aesthetics of disappearance,

which reside in memory, nostalgia and our imaginations.

Novalis’s quote “philosophy is really a nostalgic desire

to be at home” points to a fundamental truth about memory

being bound up in nostalgia that is also beautifully alluded to

in another quote from Proust’s Swann’s Way; “When nothing

else subsists from the past, after the people are dead, after the

things are broken and scattered… the smell and taste of things

remain poised a long time, like souls…bearing resiliently tiny

and almost impalpable drops of their essence, the immense

edifice of memory”. Thus the question arises; how can a

museum in space help to create a sense of belonging contained

within our memories? As with any movement of humanity into

newly colonised land (or space) there is traumatic disjuncture

with a new environment. Historically when any civilisation

repositions in new territory, it carries a raft of problems, not

least is the equating of this new territory as home. As Stephen

Muecke puts it, “…existence of course is precarious, but never

more so than when it is conceived as being without attachment

or belonging” [5].

The current world crises in refugee movement and

migration have brought this problem into sharp focus. The

authors propose that similar to the movement of migration

people need to carry their culture with them and therefore

cultural cargoes must be made manageable in order for

space needs to be addressed. Thus another question arises;

is it through dualities and ambiguities that some of these

issues can be viewed via shifting perspectives? As discussed

above, Michaloudis’s and Hance’s research and resultant

works contain dualities of meanings and overlays of cultural

signifiers. Both artists use the ideas of tourist souvenirs kept

and things or traces left behind as their primary subject matter.

These processes point to new ways of registering memory as

traces, taste or scents and in non-written way as in the initial

description of terroir and nostalgia.

The mention of the non-written invokes association

to memories, which are embodied in the oral traditions of

Indigenous peoples. Indigenous culture binds the visual

image to the important stories and natural sciences. The

absence of the written word within these cultures allow a

special profundity that is never forgotten simply because it

must always be retained as memory. The image of the rock

painting of Wandjina in the Kimberley is an excellent example

of knowledge and cultural memory bound into a single image

the image itself being the primary language, which contains

the spiritual values of the Dreamtime interwoven with the

physical aspect of the earth-bound timing of the arrival of

the wet season [6]. The increase in humidity make its earth

colours much more vivid at this period making the image

“live”. These images are “sets of symbols used to communicate

meanings developed into a symbolic universe, in which art,

language, myth and religion (are) were interwoven …” [6]. The

implication is that the more we rely solely on recorded data,

the more our memories atrophy. It is hoped that any museum

of the future could include similar artistic memories as well

as other records/ artefacts of natural history, science and

cultural cargoes from earth.

The Museum of the Future

The Museum of the Future

Is it perhaps then that through the eyes of artists who

proposes the selection of what constitutes the museum of the

future in its relation to the cultural memories of earth are to be

addressed. In the past, such artists have considered a museum

of the future as André Malreaux in 1967, who proposed in

his “museum without walls” that photographic records of

all important cultural artefacts be placed in a space as an

economic and weightless record [7]. Similarly, it is proposed

that a museum of the future would utilize new processes that

apply or have been developed out of space age technologies that

are also weightless and economic in size. An excellent example

of an artist creating work from new material is embodied

Michaloudis’s sculptures made from the space material silica

aerogel, reiterate that the artist’s muse is the cosmos itself,

coupled with the space technology that produced the silica

aerogel [8]. Souvenirs and “souveniring” has always been the

tangible evidence of tourism and the leaving behind of evidence

or tourist memento states that “I was (t)here”. The other notion

that seems to drive such activities is the need to turn the

“nowhere” of a remote place or space into “somewhere” [9].

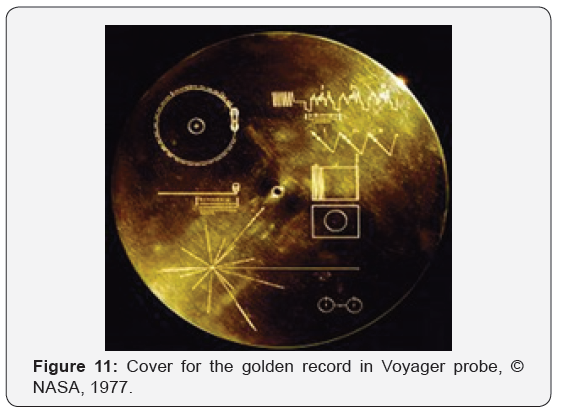

The golden disc sent out into the cosmos on Voyager in 1977

of course sends out a different message that of we are /were

here (Figure 11). The “were here” holds a particular poignancy

of the nostalgic. The point being here that material souvenirs

are very different from memories, and the author’s hypothesis

asks whether the artists working in the peripheral are in a

suitable position to think about a “collection” of the whole; say

of digital memories and works of art in space age materials,

not only souvenirs in their materiality (Figure 12). So, it is in

the digital copy of digital copy of an analogue copy (or material

copy) together with three –dimensional works are made from

aerogel and/or other media creates the constraints for a new

visual environment. Weightless media is in itself a type of

memory or souvenir that we propose to be a light and colour

soaked “apparition” constituting the artwork left behind or disappearing from Earth. The poetic interpretations of space

fused into the working of materiality as a concept within the

various mediums discussed here in the works of Michaloudis

and Hance point to a new way of representing works of art

as memory, and a different perspective on the possibilities of

storing cultural cargoes.

These possibilities of storage extend outside their function

as merely souvenirs from Earth to suggest their ability to

also manifest as profound memories. As these materials and

copies are the lightest and most spatially economic mediums

known to date, they are eminently suitable to be housed in a

CosMuseum the museum of the future. CosMuseum is imagined

as a virtual and universal museum. Its collection is created

as a data bank sculpted from an aggregate of museum digital

data, developed in a unified structure by the global museum

community and enabled through virtual transmission into the

cosmos. CosMuseum opens up the possibility of a narrative

environment that is representative of our collective humanity,

unbounded by temporality, and made accessible to an audience

both known and unknown. It is destined to provide a space

symbolic of our times, one that acknowledges the incognisant

of the present. Simultaneously the museum posits a vision

towards a timeless future, in which visitors in space may

process visual and sensory cues in ways we cannot control,

imagine or predict. CosMuseum is envisaged to contain the

memory of our present, almost as simulacra of Earth’s cultural

and environmental history, for a future time of enduring

uncertainty.

Two ventures pioneer the messaging in space of our

civilisation and are precursors to concepts broadened in the

CosMuseum: The nomadic Voyager probe launched in 1977

included sound and image captures in CD prototype that Jimmy

Carter, then President of America, introduced as: “This is a

present from a small, distant world, a token of our sounds, our

science, our images, our music, our thoughts and our feelings.

We are attempting to survive our time so we may live into yours”

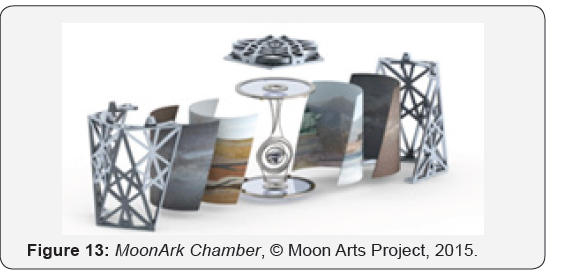

[10]. And the Moon Arts Project, scheduled for launch in 2016.

It delivers a technically advanced four chambered time capsule

to the Moon establishing a permanent ‘cultural heritage site’,

containing a discrete selection of items representative of all

Arts and Humanities with considered ‘potential to last many

millions if not billions of years’ [11] (Figure 13). Significantly,

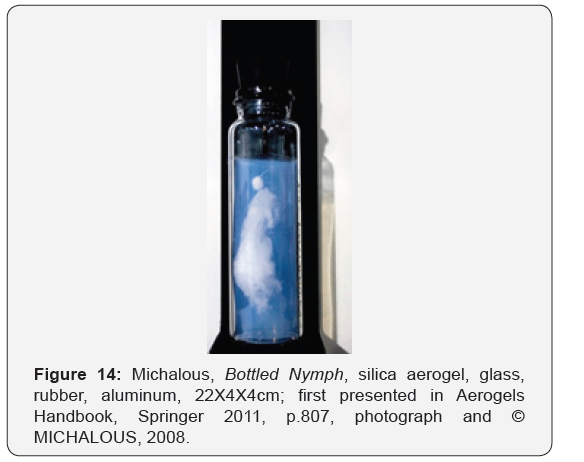

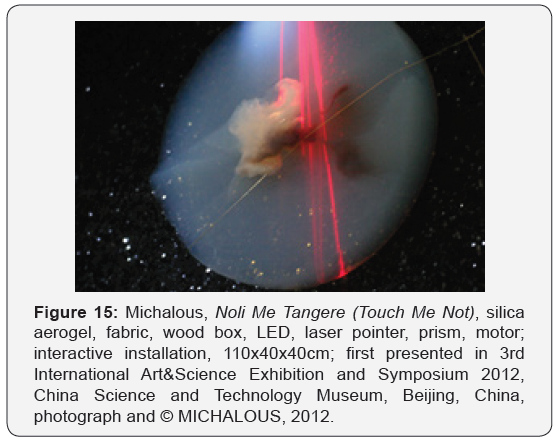

two artworks of the author, Bottled Nymph and Noli Me Tangere

are selected to be included to this project that provide an

intersect between the present and the future through their use

of an evolved medium, one that has origins in space science itself

(Figures 14&15). Their “otherworldly’ qualities, both ethereal

and cosmic, combine to empower them as objects which speak

of an endless ‘generative process of making meaning, making

story, and understanding time’ [12].

CosMuseum expands on both space incursions through

development of a museographic approach that pursues an

encyclopaedic rather than selective compiling of cultural

data. This approach transgresses discourse between art

forms, cultures, politics and geographic regions to present a

pluralistic expression in virtual format of our humanity and

collective history. The basis for a cultural databank as required

for the collection of CosMuseum can be advanced through the

development of a number of cultural collection aggregators.

Known and operable examples include: ‘Trove [13], Digital

Public Library of America [14] and Europeana [15,16]. Each of

these platforms provides digital access to collective cultural

resources that cumulatively amount to almost 600 million

items. A formal ontology prepared by the International Council

of Museums (ICOM) through its International Committee for

Documentation (CIDOC) provides a conceptual framework for

integration of cultural data between disparate and diverse holdings [17]. Inclusive development of global content will

take many decades to achieve. Consistent data standards,

collaboratively applied in a sovereign approach across a global

museum sector would provide an apparatus for expansion

and centralised development of a globalised digital cultural

heritage hub from which CosMuseum would continue to build

and to draw its content for future transmission. While digital

access as a process is a dissociation from the material in

form and presence, the proliferation and mass of digitisation

projects have already altered the cultural landscape in which

museum collections are accessed across shared platforms.

This changing access enables multiple associations

and interpretations to generate. CosMuseum redefines the

authentic to include its digital derivative and in doing so,

enables on-going authorship of meaning and encapsulation of

memory by association. Collections vulnerable to catastrophe,

degeneration, decay, neglect or disinterest prevail through

preservation albeit in altered or immaterial digital form/s. The

concept is challenging to our traditional view of a museum as

a repository filled with objects maintained in original form

and functioning as true and authentic expressions of our

earthbound civilisation which are illuminated in a vocabulary

structured by the ideological constraints of our time. Embedded

meanings associated with concepts, memories, traditions,

ritual, spirituality and technical or artistic achievements are

subliminal as the resemblance or presence of an object in

CosMuseum bears its own significance. Material composition

becomes secondary to its being in CosMuseum through the act

of placement and transmission.

In juxtaposition to mineral compositions that have

long preserved the evidence of our human settlement, the

immaterial in virtual or newly envisaged formats becomes

the evolved embalming tinctures in which the evidence of

our civilization can be cradled. CosMuseum proposes that

it is possible for reality to be realised at any one moment in

time. The artist Grayson Perry expressed a similar sentiment

in regard to uncontrived narratives during his exhibition of

works at the British Museum in 2011: “That I am an artist and

not a historian and this is an art exhibition does not mean it is

any less real. Reality can be new as well as old, poetic as well

as factual and funny as well as grim” [18]. Through aesthetic

forms, in a sensory language, the CosMuseum provides a

platform to experience and to remember. Development of

CosMuseum is precipitated by an alliance between the museum

sector and space science to innovate the project and realise

technology that creates a future sustained within the universe,

in which evidence of our collective humanity poses an enduring

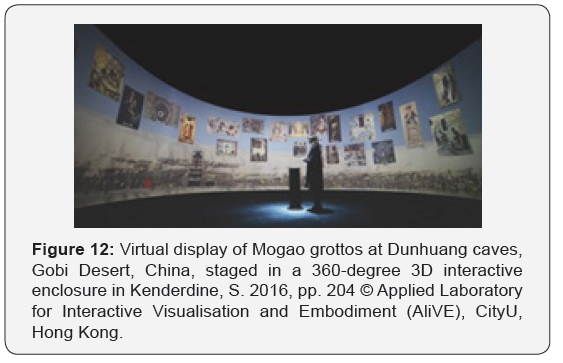

imprint. In visualizing CosMuseum examples of virtual and

interactive enclosures developed by Kenderdine and team can

be seen which enable access to cultural landscapes and museum

collections in previously unimagined detail and resolution [19].

CosMuseum creates a virtual landscape through both its digital

architecture and through its adaptive use of trans-disciplinary

digital technology that holds the potential to recreate the now

in the future. CosMuseum c ould b e l ocated e ither i n a f ixed

position or as a nomadic object traversing the cosmos, subject

to technical challenges in space technology and its ability to

facilitate the selected global collective resources including:

data transmission, data access and operability in a timeless

and sustainable projection. As weight and weighted matter

is a discerning feature to what could feasibly be included to

a museum in the cosmos, emergence of new media explores

the possibility of conversion not just in digital formats but

also in weightless space materials such as aerogel adapted by

Michaloudis in creation of his works. Any increase in range

of payload available to space travel could include original or

replicated forms to CosMuseum that would no doubt enhance

humankind’s physical presence within the Cosmos.

In concept, the CosMuseum holds a belief in the ‘numinous’

[12] experience posed through interaction with museum

objects that metaphorically transport observers beyond the

self as new meanings and narratives are contemplated over

time and space, perhaps without possibility of being anchored

to the reference to the now. Objects in the CosMuseum are as

pilgrims on a journey that bear witness to our existence and

evolution. In this way, there are similarities to object-centred

museums purposed to make ’sense of our world by discovering

and interpreting the past and present for the future’ [20].

Aestheticism- as the principal agent- is designed to transmit a

sensory expression that in examples of works by Michaloudis

and Hance have their origins in the periphery, in prehistory, and

from a region once perceived as terra nullius that paradoxically

holds evidence of the longest continuous human settlement on

this planet [21-23]. A fitting inclusion to a cultural package on

a journey as yet not fully realized [24,25].

Conclusion

The CosMuseum project is a realisation of our earthly frailty

and undeterminable future. It proposes a migratory pathway

through which the evidence of our civilisation can journey.

Works by both artists are embedded with symbolism and meaning and provide example of the profundity concealed and

expressed in material and immaterial forms that transgress

time. The tension created through conceptualisation of cultural

loss is abated through possibility of preservation and sanctity

found within carriage of CosMuseum. Concepts of preservation

are shown to be achievable through projects like MoonArts

and other digital technologies in which museum collections

are accessed and interpreted. New weightless materials such

as silica aerogel allow new original works to be included in

the CosMuseum as well as forming simulacra that encapsulate

memories of other earthbound art works. It has been shown

that these cultural cargoes embedded in a new Aestheticism of

the Digital are true and authentic works-memories as well as

being souvenirs from planet Earth.

To Know More About Trends in Technical and ScientificResearch click on: https://juniperpublishers.com/ttsr/index.php

To Know More About Open Access Journals Please click on:

Comments

Post a Comment